HISTORY OF THE CANONICAL AREA OF THE EPARCHY OF SREM

ANCIENT SIRMIUM, CHRISTIAN MARTYRS AND THE FIRST BISHOPS

The Eparchy of Srem is an Orthodox ecclesiastical region which, like the entire geographical area where it carries out its salvation mission, bears the name derived from the Roman city of Sirmium, over whose ruins today’s Sremska Mitrovica was built. The existence of Sirmium was first recorded six years after the birth of Christ, during the Illyrian rebellion and even then it was noted for its convenient strategic position. The proximity of the busy Roman roads soon enabled it to establish close trade ties with the rich Aquileia, but also gather serious support from the warlike rulers of the Empire, who saw in it a useful military stronghold against the enemy Dacia. At the end of the 1st century, it enjoyed the status of a colony, while in the second half of the 3rd and the first half of the 4th century, it was described as an advanced settlement and the center of the province of Pannonia II. Even coins were minted here from 330 to 395, including the most important ones, those made of gold (379).

Sirmium, like Milan, Nicomedia or Trier, also served as a temporary capital of certain emperors. The notorious empress Faustus visited her husband, Marcus Aurelius, in Sirmium in 170 and 171 and several Roman rulers were born in or around the city itself: Trajan Decius, Maximian Herculius, Aurelian and Probus. Some historians claim that this administrative center of Illyricum is also the birthplace of the emperors Constantius II and Gratian. In addition, two or three Augusts lost their lives there, Claudius Gothicus, who died during the plague epidemic, and Probus, who was killed by his own soldiers in his native region. Nevertheless, Philostratus adds the emperor-philosopher Marcus Aurelius to this sad list. Edward Gibbon wrote about the important civilizing role played by the tragic emperor Probus in the “wild Srem” and how, while trying to save the soldiers from the pernicious temptations of idleness and laziness, he employed his legions to cover the Alma Mons (“Fruška gora”), located in the region where he was born, with rich vineyards. Emperor Maximinus the Thracian spent many years in this city, fighting against the Sarmatians, while Maximian Herculius even built a private villa in its immediate vicinity, modeling himself after his elder ruler Diocletian, who, after voluntary abdication, retired to his native Dalmatia. After Diocletian’s introduction of the tetrarchy at the end of the 3rd century, the cruel Caesar Galerius ruled his quarter of the Empire from the Sirmian court. Later, the Holy Emperor Constantine, Constantius II, Julian the Apostate, but also Theodoric the Great, the mighty destroyer of the ancient world, stayed there.

It is only logical that Christianity began to spread very early in such a famous, imperial city. Some old, though scientifically unconfirmed, traditions link the establishment of the first church organization in this area to the apostolic times, stating that the Holy Apostle Peter ordained his disciple Epenetus as a bishop in Sirmium, while the Holy Apostle Paul sent Saint Andronicus here, appointing him as the archpastor of Sirmium. Nevertheless, it is now considered that the first local bishop for whose episcopal service there is reliable evidence was St. Irenaeus of Sirmium, who was martyred in The Great Persecution, launched by the Emperor Diocletian in 304. His passion testifies that, while he was lying in a Roman dungeon, exposed to cruel physical torture, the caring members of his family, crying and wailing, begged him to renounce his faith and thus save himself and them from unbearable torment and suffering, which he quietly but firmly refused, citing the Holy Scriptures. Probus, the governor of Pannonia, realizing that he would not succeed in his intention to force this Holy Martyr to offer an impure sacrifice to the Roman deities, ordered that he be beheaded and thrown from the Bassent Bridge into the Sava River.

The ferocity of Diocletian’s and Maximian’s persecutions in the area of today’s Srem may point to the existence of a numerous, orderly and zealous Christian community. In addition to Saint Bishop Irenaeus, his contemporaries, deacon Dimitrije, gardener Synerot, Saint Anastasia, whose cult was transferred to Rome and Zadar, Hermagoras (or Hermogenes, due to an error in the transcription) as well as five girls, whose names are now forgotten, also witnessed for Christ here, shedding their own blood. Martyrologists also mention Fortunatus, Donatus, Basilius and Timotechus, while, according to some authors, Srem, during the Roman persecutions, gave over 200 martyrs to Christianity. The priest Montanus and his wife Maxima from Singidunum (present-day Belgrade), Pollio from Cibala, Saint Quirinus from Siscia (present-day Sisak) and 40 other Christians, whose names are preserved or unknown, were also executed in Sirmium. Furthermore, prayerfully remembered are the “Martyrs of Fruška gora”, the four stonecutters, Claudius, Castor, Sympronian and Nicostratus, who, judging by the Passio quatuor coronatorum, lost their lives under Emperor Galerius, because of their persistent refusal to carve the image of a pagan idol Aesculapius during the visit of Augustus Diocletian.

Church life in Sirmium seems to have flourished in the historical period that followed the Edict of Milan in 313 AD. Churches of St. Sinerot and St. Anastasia were built, as well as the temple dedicated to St. Demetrius of Thessaloniki, which Dimitrije Ruvarac claims existed “during the Roman and Byzantine rule” and which is later found in writings from the 14th century. In the following centuries, when barbarian invasions almost completely erased the historical memory of the disappearing Roman population, the monastery of St. Demetrius will give its name to the former imperial city (civitas s. Demetrii). Archaeological research in the northeastern Mitrovica necropolis revealed a smaller, single-nave temple with graves from the time of Emperor Constantius II, where, in the immediate vicinity of the altar apse, there is an inscription beginning with the words: “In basilica domini nostri Erenei”, which leads to the conclusion that the cult of this saint and martyr very early began to develop in Sirmium.

Another Sirmian bishop that was written about is Domnus (from 325 to about 335), a participant in the First Council in Nicaea and an ardent follower of the ideas of the Alexandrian archbishop Athanasius the Great. It is he who mentions Domnus, as a victim of the anti-Nicene reaction, which overthrew him from the episcopal seat, although they did not manage to shake his determined orthodoxy, even after 330. He was probably a bishop or even a metropolitan of the entire Pannonian region, whom the emperor Constantine himself knew personally, while he stayed in Sirmium in the period around and before the Council. He was succeeded by Eutherius, who confirmed his orthodoxy at the Council of Serdica in 343 by speaking out against the teachings of the Alexandrian presbyter Arius, who “starting from monotheistic views, refused to accept the equality of the Father and the Son.” It seems that the ancient beginnings of the divinely protected Eparchy of Srem and its canonical area, like the beginnings of the Church itself, were marked by difficult dilemmas and painful trials, especially after the charismatic Arius spent some time in Illyricum, building a firm foothold for the heretic church in the area of today’s Srem. In 351 AD, under the Arian emperor Constantius II, a more compromising current of this heresy, known as the Semi-Arianism, introduced the first of four variants of the so-called “Syrmian formula” of faith. In the following years, a whole series of “councils and synods” were organized there, where heated discussions were held with rigid Arians and Orthodox bishops, while at the councils in Sirmium and Rimini, Arianism was declared the state religion in 359. The provincial town gained a dominant role in the heated Christological discussions, primarily due to the fact that it was the seat of Emperor Constantius II at the time.

The next in the line of ancient archpastors of Srem was Photinus (elected no later than 344), a student of Marcellus of Ancyra, a gifted preacher, a celebrated erudite, the author of several important works and, finally, the founder of a new heresy, named after him (“Photinian”). The teachings of Bishop Photinus, who was accused of “falling into Paulism and self-righteousness”, were rejected by both the Orthodox and the Arians, and he was deposed from the archbishop’s chair for the first time at the Council of Sirmium in 351. The vacillation between Arius’ heresy and orthodoxy was felt in this diocese under the newly elected bishop Germinius, who wore his miter as an Arian and came quite close to Orthodoxy by 366, although this spiritual evolution can also be interpreted as related to the Orthodox Emperor Valentinian’s coming to the throne, two years before his definitive theological reversal. Then Emperor Julian the Apostate restored all the deposed archbishops, including Photinus. In the end, the omophorion of the Sirmian Bishops was entrusted to Anemius (from 376 to about 392), who, as a confirmed supporter of the Nicene Creed, completely eradicated Arianism in his area.

The Metropolitanate of Sirmium in the middle ages

Ironically, it was at the Council held in Sirmium in 378, under the presidency of the orthodox bishop Anemius, where Arianism definitively condemned and banned and three years later, it was recorded that not one of their places of worship could be found in all of Illyricum. The administration of this capable archbishop coincided with the reign of Theodosius I, whom the Emperor Gratian, in 379, again in Sirmium, proclaimed as Augustus of the eastern part of the Empire and who, later, with great zeal persecuted the remnants of pagan religions and heretical sects. The eparchy reached its zenith under such a distinguished Hierarch, who enjoyed the high status of metropolitan (episcopus metropolitanus). Among the signatories of the conclusions reached at the Councils in Aquileia and Rome, in 381 and 382, he was also titled as “caput Illyrici, thereby qualifying Sirmium as caput totus Illyrici”. In the epistle of the Church Council of Constantinople addressed to the Council of Rome, held 382, Bishop Anemius is listed immediately below Metropolitan Aholius of Thessaloniki, above whom only the archbishops of Rome, Mediolanum and Aquileia are mentioned. However, currently there is no data that would point to the conclusion that this title implied any higher jurisdiction than the metropolitan one, so it is considered that it was essentially of an honorary character.

During the same period, the influence of Saint Ambrose of Mediolanus (339-397, bishop from 374), as one of the leading figures of the Western Roman Empire and the metropolitan of its capital, Milan (Mediolanum), went beyond the borders of the Vicariate of Italy and even reached the distant Pannonian provinces. In this sense, the indisputable authority of the fearless Father of the Church, who did not hesitate to impose a heavy and just penance on Emperor Theodosius the Great himself, because of the Thessaloniki massacre, is also witnessed by the bishop of Sirmium, whom he ordained. It was probably Cornelius (392–409), who, after Anemius’ death, inherited the chair. There are some later mentions of Laurentius, at the beginning of the 5th century, and Sevastian, who is assumed to have been high priest around 591, though it is more likely that he was the bishop of Risan. To the great regret of historians, the names of the other eparchs of Srem have been lost in the opaque fog of human oblivion. Historian Priscus is the only one who incidentally mentions the bad luck of the unnamed bishop of Sirmium, who, during the Hun siege of the city in 441, took out several golden ecclesiastical valuables from the treasury of his cathedral temple, in order to serve him as a ransom, in case he fell into barbarian captivity. It seems that, in the end, he was tricked, because he entrusted the expensive items to a person who, a little later, pawned them with a banker in Rome and thus secured a lucrative loan for himself, leaving the cautious hierarch to his uncertain fate.

Dramatic theological rifts of the 4th century also left some precious antiquities to future generations, especially when it comes to church literature and traditional copying activities. The Evangeliarium Sirmiense, written in uncial script, most likely for the needs of the Arian Church, is still kept in the State Library in Munich. According to some data, during the time of Germanic domination over Sirmium, from 536, a Gepid Arian bishop resided here and, during the time of the Huns and Goths, the aforementioned church exerted a significant influence on the neighboring nations as well. The only Arian bishop known by name, Trasarich, took considerable treasure to Constantinople after the collapse of his state in 567, while the duration of this cathedral seat is also evidenced by a later medieval German letter, in which Pilgrim from Passau claims to the Roman Pope that the Gepids founded seven bishoprics in Eastern Pannonia and Moesia, among them the one of Sirmium.

Sirmium irretrievably lost the enviable rank it acquired in the first period of its history, until Justinian I (527–565) formed a new church organization in this area, with its seat in the newly founded city of Iustiniana Prima. According to the provision of his novel from 535, the created archbishopric also included part of the province of Pannonia Secunda, with the episcopal seat in the city of Bassiana, located between Mitrovica and Zemun. This eparchy, which was governed by hitherto unknown hierarchs, then belonged to the sphere of Latin, Roman culture, with a slight admixture of surviving Hellenic traditions. It is interesting that the Illyrian bishops of that time regularly represented the opposition to the emperor’s church policy, as well as his decisive theocratic and Caesaropapist style of rule. The rebellious episcopate even excommunicated its head, Benenatus the archbishop of Justiniana Prima, for adopting official Constantinople positions, contrary to the opinion of his brothers, the Illyrian and Pannonian archbishops. Furthermore, just before the Fifth Ecumenical Council was held in 553, civil unrest broke out here and was suppressed only after military intervention.

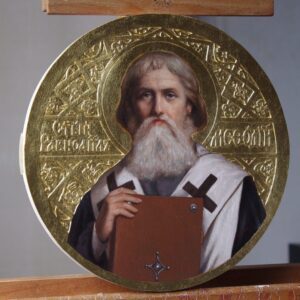

As the Bishop of Srem Dr Andrej (Frušić) pointed out many centuries later: “Sirmium flourished as a Metropolitanate in the Eastern Roman Empire until 582, when it was overthrown by the Avars. Then everything stopped, and the memory of Sirmium remained only in the official title of Saint Methodius, the teacher of Slavs.” Namely, there is a theory according to which, before 880, Pope Hadrian II appointed Saint Methodius as the bishop of Sirmium. This is concluded based on the known information that he was entrusted with the “seat of Saint Andronicus”. Sirmium almost certainly represented only the titular seat of this diocese, under whose jurisdiction was Pannonia, Belgrade, as well as the former Serbia of Prince Mutimir.

The arrival of the Hungarians in the Pannonian Plain completely changed the ethnic, cultural and social image of the Carpathian Basin. Except for some circumstantial information, we know almost nothing about the position of Sirmium and its Slavic population, which had already largely settled there. Early Hungary was under the strong influence of Byzantium and the Eastern Church, and Dušan J. Popović long ago expressed the view that, during the 10th century, the Greek monastery in Sremska Mitrovica was the spiritual center of both Hungarians and Serbs, i.e. Slavs living in Srem and Bačka, who accepted Christianity at that time. This could refer to the holy place which will later be the seat of the Bishopric of Srem, apparently founded in the time of Saint Stefan, for monks of Greek, Hungarian and Slavic ethnicity. Theophylact, the bishop of Tourkia (Byzantine name for Hungary), had an image of Saint Demetrius on both sides of his seal, around which was written: “God help Theophylact, bishop of Tourkia.” His successor, Antonius, also imprinted the same saint on his documents.

METROPOLITANATE OF BELGRADE-SREM AND DESPOTS OF SREM

After the collapse of the Serbian medieval state in Kosovo in 1389, migrations of Serbs to the north became more frequent. This resulted in Srem taking on an even more visible Orthodox character. After the heavy defeat against Sultan Bayazit I in the Battle of Angora in 1402, the despot Stefan Lazarević recognized the supreme authority of the Hungarian king Sigismund and in return received a feudal estate, which included all the important cities of Srem, Kupinik (Kupinovo), Zemun, Mitrovica and Slankamen. Of the archpastors who managed the spiritual life of the Serbs in Srem from the reign of Stefan Lazarević until the ordination of the Holy Metropolitan Maksim (Branković), today we know about Isidor, a skilled diplomat and protector of the interests of Dubrovnik merchants at the despot’s court; Grigorije, about whom there is no other information apart from his name; Joanikije (1479), who exempted the Vlach priests in the Marmara County from levies; Filotije (1481), mentioned in the record of Pope John on the Belgrade Four Gospels, during the time of Despot Vuk; Grigorije II, whose more detailed biographical data is also lost, and TeofaQn (ca. 1504–1509), whose modest material position forced him to ask for help from the Grand Duke of Moscow Vasiliy III Ivanovich (1503–1533).

In 1427, the despotic throne of Stefan Lazarević was succeeded by Đurađ Branković, who had previously taken an oath to King Sigismund in Belgrade. Already in the thirties of the 15th century, Srem and the Vukovar County were counted as Serbian regions, with over 200,000 inhabitants, which was about six percent of the total population of the then Hungarian state (on a Venetian map from 1564, Srem was drawn as Raška (Rascia)). In order to strengthen the southern regions of the endangered Monarchy, King Matthias Corvinus appointed Đurađ’s grandson (and son of the blind Grgur Branković) Vuk, as the master of his Orthodox vassals in 1471, giving him the estates of Kupinik, Slankamen, Berkasovo and Irig. After the death of Vuk in 1489, he appointed Vuk’s cousin, Đorđe to be the Serbian despot. He was the second grandson of the despot Đurađ and the son of another prince blinded in the sultan’s palace, Stefan Branković, from his marriage to Angelina, the daughter of the Albanian magnate George Arian Komnen Topia Golem and the “sister-in-law of Skanderbeg”.

Đorđe’s blind father, shortly after his death in 1476, was canonized in Belgrado, Friuli, in the former Republic of Venice. The relics of Saint Stefan were laid by the young despot and his mother Angelina in the temple of Saint Apostle Luke in the capital of Srem, Kupinik, after meeting with King Matthias, thus laying the foundation on which the cult of the so-called “national sanctity” would later develop. Đorđe Branković, the despot of that time, is the most praiseworthy for the religious respect that would later be shown to the members of this exceptional dynasty. As some researchers conclude, by refusing to marry the Roman Catholic Isabella from the Aragonese dynasty of Naples and a cousin of the Hungarian Queen Beatrice, Đorđe abdicated the throne in favor of his brother Jovan. He was then ordained a monk by the hegumen of the Gornjak Monastery, naming him Maksim, in 1496. He was ordained to the rank of hierodeacon and hieromonk by Metropolitan Kalevit of Sofia, in Kupinik, in 1500. After the death of despot Jovan in 1502, he moved to Wallachia with his mother Angelina and took the mortal remains of his father and his brother with him. He traveled to the neighboring Orthodox country in order to answer the plea of the Wallachian duke Jovan Radul IV the Great to contribute to the church life there with his ruling experience and inviolable moral authority. Here, the deposed Patriarch of Constantinople, Nephon (1497–1498), consecrated him as an archbishop, around 1505.

Saint Maksim is certainly one of the most prominent figures of the Serbian Church. His name is associated with the establishment of the first printing house in Wallachia, where the monk Makarije from Montenegro worked. He left the Wallachian archbishopric after the death of Duke Radul and returned to Srem from Buda in 1508, where he became the Metropolitan of Belgrade-Srem. He was mentioned as a Metropolitan for the first time on August 11, 1513, in the book of Apostles with interpretations, written in Slankamen by Andrija Rusin from Sanok. Metropolitan Maksim proved to be a good organizer in this “semi-independent” diocese, under the supreme authority of the Patriarch of Constantinople. He initiated or wholeheartedly helped build and rebuild monasteries, not only in Srem, but also in Banat, even while he was serving his people as a despot. Having received substantial financial aid from the Wallachian Duke Jovan Njagoj, he built the Krušedol Monastery, which he used as a metropolitan residence. He equipped it with an exceptional family library of the deceased Branković despots, ordering the famous “Maxim’s Gospel”, written in 1514, from the Krušedol monk Pankratije.

Before the restoration of the Patriarchate of Peć, all Serbs north of the Sava and Danube were subjects of only one diocese, the Metropolitanate of Belgrade-Srem, with a vicariate in Ineu (Jenopolje). Patriarch Makarije, trying to reduce the inevitable distance that existed between the majority of the faithful and their overburdened archbishop, founded the dioceses of Bačka, Slavonia, Lipovo, Vršac and Buda. The archpastors of the first five dioceses each held one carved seat in the apse of Hopovo, which, according to Dr. Grujić, led to the conclusion that the monastery then served as the second residence of the Belgrade-Srem metropolitans, whose line of succession, during the time of the Turkish occupation, is now completely impossible reconstruct.

THE METROPOLITANATE OF KARLOVCI

The Metropolitanate of Karlovci is certainly one of the most prominent and meritorious institutions of the Serbian Orthodox Church. It is an ecclesiastical region that, by 1920, included all Orthodox Serbs in Vojvodina, Slavonia and Croatia, i.e. members of this nation who, since the end of the 17th century, inhabited the Habsburg Monarchy. Serbs also made up a large part of the population of these areas before the creation of the Metropolitanate, and their number increased after the Habsburg wars with the Turks, which caused a series of migrations in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. In terms of the number of settlers and the importance of the privileges received from the Habsburg Emperor Leopold I, the emigration under the leadership of the Patriarch of Peć, Arsenije III Čarnojević, in 1689 and 1690, is of particular importance. The imperial privileges issued to Patriarch Arsenije regulated the freedom of Orthodox worship and the unhindered use of the Julian calendar, while the Church hierarchy was guaranteed all the rights it enjoyed in the Ottoman Empire. According to those provisions, the archbishop represents the supreme authority in the Orthodox Church and governs the people, appoints metropolitans, bishops, hegumens and priests, builds temples and monasteries, and this dignity could only be obtained by an ethnic Serb, elected by the church-national assembly. On August 20, 1691, based on the privileges that the hierarchy received from the Ottoman sultans, Emperor Leopold I added that the archbishop enjoys a decisive political influence on the secular life of his compatriots, while Serbs in towns and villages are allowed to organize secular institutions under the administration of public authorities, magistrates.

After the Great Migration, the heads of the Serbian Orthodox Church lived in monasteries. Since 1708, Metropolitan Isaija Đaković resided in the Krušedol monastery, but already from the following year, the archbishops started residing in Karlovci. This choice, made in 1713, is somewhat logical, considering that Srem was a central region at that time, with a majority Orthodox population. The metropolitans of Karlovci also held the title of Serbian archbishops, which was confirmed and recognized by the imperial privileges of the Habsburg Monarchy from 1690 and 1691. The civilizing mission of the Orthodox hierarchy in enlightening and gradually cultivating their flock, benighted in many respects, after the long and bloody Turkish tyranny, is especially important. Thus, in 1726, the church-national assembly decided that every bishop was obliged to open schools within his diocese, while the very next year Metropolitan Mojsije Petrović urged for an approval by the imperial court that his compatriots could freely establish higher and lower schools. Metropolitan Pavle Nenadović founded the Latin and Lower Clerical Schools, while in 1791, in addition to the noble benefactor Dimitrije Anastasijević Sabov, Metropolitan Stefan Stratimirović, who also founded the Karlovci Seminary in 1794, was most responsible for the establishment of the Karlovci Gymnasium.

As already mentioned, the Metropolitanate of Karlovci was governed by superiors with the title of Metropolitan of Karlovci and Archbishop of Serbia. The exceptions were the patriarchs of Peć, Arsenije III Čarnojević and Arsenije IV Jovanović Šakabenta. Both of them led large migrations of Serbs to the Habsburg Monarchy and they governed the Metropolitanate of Karlovci under the title of Patriarch, which they also held in “Old Serbia” and “which was recognized by the Habsburg Monarchy as the first Privileges they received.” However, Karlovci truly became the seat of the Patriarchate only after Metropolitan Josif Rajačić was proclaimed patriarch at the May Assembly in 1848, which was confirmed by the manifesto of Emperor Franz Joseph on December 15, 1848. This title was held by the superiors of the Metropolitanate of Karlovci until the mysterious and violent death of Patriarch Lukijan Bogdanović in the Austrian spa town of Badgastein, in 1913.

SREM IN THE UNITED SERBIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was proclaimed on December 1, 1918, finally removing the last obstacles to the desired unification of all provincial Orthodox churches, which, until then, existed in different, more or less tolerant, states with a different state religion. Due to these natural aspirations, the first conference of Serbian bishops was convened in Sremski Karlovci on December 18 (31), 1918, at which a decision was made on the “sanative intention” of founding the Serbian Patriarchate. The first two decisions on unification with the other Serbian Churches in the Kingdom of Serbia, Montenegro and Dalmatia, were read. They were made by the bishops of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Holy Synod of Archbishops of Metropolitanate of Karlovci. The decision of the hierarchy to unite into the Serbian Orthodox Church was announced by the regent Aleksandar Karađorđević, with a royal decree dated June 17, 1920. The unification of the Serbian Orthodox ecclesiastical regions was carried out in Belgrade on May 13 (26) 1919, while the proclamation of the Patriarchate took place in the throne room of the Patriarchal Palace in Sremski Karlovci on August 30 (September 12) 1920, in a very solemn manner. Its establishment was previously, on September 10, adopted by acclamation of the members of the Holy Synod of Bishops. Here, in fact, the Peć Patriarchate was restored, which was very significant, because this was the only for way for the united Church to regain its old rank in the Orthodox world. After that historic act, it was possible to access the procedure, ceremonies and rites, which accompany the election and enthronement of its head. After the election, in which 94 voters were present, on November 30 (November 12) 1920, 83 votes were won by the Archbishop of Belgrade and Metropolitan of Serbia Dimitrije (Pavlović). It was determined in the Confirmation Decree that his seat would be in Belgrade, while Sremski Karlovci was designated as his temporary seat.

As a Metropolitan of Belgrade-Karlovica, Patriarch Dimitrije managed the territory of today’s Diocese of Srem as the eparchial archbishop and Dr. Maksimilian (Hajdin), born in Novi Sad in 1879, was appointed as the first Vicar Bishop of Srem, or rather Sremska Mitrovica, as his title read. When he was elected Bishop of Dalmatia-Istria at the end of 1928, the Vicar of Srem became an assistant professor at the Faculty of Theology in Belgrade, Dr. Irinej (Đorđević). Patriarch Dimitrije passed away on April 6, 1930, while six days later, on Lazarus Saturday, he was succeeded on the throne of Saint Sava by Metropolitan Varnava (Rosić) of Skopje. Under him, after the relocation of the seat of the patriarch and the church administration to Belgrade, in the summer of 1936, the area of the Srem diocese was completely left to the care of vicar bishops. Patriarch Varnava entrusted this dignity to Dr. Tihon (Radovanović), consecrated on November 21, 1932 in the Belgrade Cathedral a as Vicar Bishop of Srem. Two years later, he was succeeded by Archimandrite Sava (Trlajić) from Krušedol, the future Bishop of Gornji Karlovac and a martyr in the concentration camps of Independent States of Croatia. Platon (Jovanović) (1874–1941), another Krušedol archimandrite who would wear a martyr’s wreath in World War II, was appointed as the next vicar of Srem, after Saint Bishop Sava left for Belgrade. Following the example of his predecessors, on January 28, 1940, Patriarch Gavrilo (Dožić), together with Metropolitan Josif of Skopje and Bishop Vikentije of Zletovo-Strumica, ordained Archimandrite Valerijan (Pribićević) as Vicar Bishop of Srem in Sremski Karlovci. He was a long-term, very successful hegumen of the Jazak monastery, who maintained direct management of this holy place as an archbishop.

During the Second World War, Orthodox Srem survived brutal persecution, the likes of which was rarely recorded in the history of Christianity. Valerijan theVicar of Srem shared the sufferings of his flock and was constantly harassed already at the beginning of the war. He sought refuge in Split, where he left this world on July 10, 1941. The priceless artistic and cultural heritage of Srem was mercilessly looted from desecrated and burned temples and monasteries or dragged in packed wagons to Zagreb. In the memorials of the innocent victims of fascism, literally all the places of today’s Eparchy of Srem are listed, as well as the names of holy martyrs, hieromonk Platon (Bondar) from Jazak, Kiprijan (Relić) from Vera and Gavrilo (Eklenović) from Privina Glava, the Osijek priest and catechist Vojislav Vojnović, parish priest of Krnješevac Blaža Golubović, Obreš priest Vojislav Zonjić, Ozren Janošević of Beočín and archpriest of Opatovac Emilijan Josifović. Among those who carried the crown of thorns, the name of Saint Rafailo (Momčilović) (1875–1941), an academic painter and hegumen of the Šišatovac Monastery, stands out in particular. At the end of October 1944, in such frightening circumstances, the Holy Synod of Bishops entrusted the office of Vicar Bishop of Srem to Arsenius (Bradvarević) (1883–1963), the latter Metropolitan of Montenegro and the Littoral and the Bishop of Buda.

The time of Josip Broz Tito as the president of Yugoslavia marked a completely new epoch in the two-millennium duration of the Orthodox Church, which in the following decades would be persistently oppressed, robbed and humiliated, and eventually pushed to the margins of an uninterested communist society. That was the beginning of perhaps the most shameful period of the history of Srem, marked by pigsties and barns built from materials brought from the ruins of ancient sanctuaries or septic tanks covered with tombstones with heraldic signs of the noble founders of the monasteries of Fruška gora. One year after Patriarch Gavrilo returned from Nazi captivity via Prague and Karlovy Vary (on November 14, 1946) to a country gripped by tectonic social changes, the Holy Synod of Bishops was urgently convened, where he was introduced to the new, terrifying problems of the clergy and believers. The parliamentary sessions, which lasted from April 24 to May 21, 1947, resulted in the creation of new dioceses : Šumadija and Budimlja-Polim. In addition, on April 24 (May 7), the gathered archbishops made a decision to establish the Eparchy of Srem, with headquarters in Sremski Karlovci, which will include the dioceses of Osijek, Vukovar, Šid, Ilok, Sremska Mitrovica, Stara Pazova, Ruma, Sremski Karlovci and Zemun, “except for the city of Zemun, which remains part of the Archbishopric of Belgrade-Karlovci with its four parishes”.

Finally, in 1951, the former Bishop Nikanor (Iličić) of Gornji Karlovac was elected as the first archbishop of the established Eparchy of Srem. The endeavor of administrating the devastated diocese, with gaping and neglected war wounds was carried in the most difficult social circumstances by his successors, the bishops of Srem Makarije (Đorđević) (1955–1978) and Andrej (Frušić) (1980–1986). Until the eighties of the 20th century, the sites of some monasteries in Fruška Gora still resided in frightening ruins. Those monumental and sacral buildings that were not completely destroyed under the fascist occupation were usurped by inappropriate secular institutions in a communist state, completely insensitive to religious needs of its population.

ПОЗНАТИ АРХИЈЕРЕЈИ

КАНОНСКОГ ПРОСТОРА СРЕМСКЕ ЕПАРХИЈЕ

1. Епенет (по предању, први век)

2. Свети Андроник (по предању, први век)

3. Свети Иринеј Сирмијски (пострадао 304. године)

4. Домнус (325–335)

5. Еутерије (до 343)

6. Фотин (344–351)

7. Герминије (око 366)

8. Анемије (376–392)

9. Корнелије (392–409)

10. Лаврентије (почетак 5. века)

11. Неименовани епископ Сирмијума ког су Хуни одвели у

заробљеништво, 441. године

12. Севастијан (око 591)

13. Трасарих (гепидски епископ, 536–567)

14. Свети Методије, епископ на столици Светог Андроника (Сирмијума)

(постављен око 880. године)

15. Теофилакт (епископ Туркије са седиштем у граду Светог Димитрија, 10.

век)

16. Антоније (епископ Туркије са седиштем у граду Светог Димитрија, 10.

век)

17. Исидор (београдско-сремски митрополит, од 1403. године)

18. Григорије (београдско-сремски митрополит, после 1403. године)

19. Јоаникије (београдско-сремски митрополит, око 1479. године)

20. Филотије (београдско-сремски митрополит, око 1481. године)

21. Григорије II (београдско-сремски митрополит, крајем 15. века)

22. Теофан (београдско-сремски митрополит, око 1504–1509)

23. Свети архиепископ Максим Бранковић (1508–1516)

24. Серафим (сремски митрополит, пре турских освајања)

25. Роман (београдско-сремски митрополит, око 1532. године)

26. Лонгин (београдско-сремски митрополит, око 1545–48. године)

27. Јаков (београдско-сремски митрополит, око 1560. године)

28. Макарије (београдско-сремски митрополит, око 1589. године)

29. Лука (београдско-сремски митрополит, око 1599. године)

30. Јоаким (београдско-сремски митрополит, 1607–1611)

31. Висарион (београдско-сремски митрополит, око 1612. године)

32. Теодор (београдско-сремски митрополит, око 1623–28 године)

33. Авесалом (београдско-сремски митрополит, око 1631. године)

34. Хаџи Симеон (београдско-сремски митрополит, око 1640. године)

35. Јосиф (викарни епископ хоповски, око 1641. године)

36. Неофит (викарни епископ хоповски, око 1641. године)

37. Михаило (викарни епископ хоповски, од 1647. године)

38. Хаџи Иларион (београдско-сремски митрополит, око 1650–62. године)

39. Јефрем (београдско-сремски митрополит, 1662–1672)

40. Елевтерије (београдско-сремски митрополит, 1673–1678)

41. Пајсије (београдско-сремски митрополит, око 1678–1680)

42. Хаџи Симеон II Љубибратић (београдско-сремски митрополит,

1682–1691)

43. Лонгин Рајић (викарни епископ хоповски, до 1688. године)

44. Арсеније III Чарнојевић (патријарх пећки, 1690 – 1706)

45. Стефан Метохијац (епископ сремски, фрушкогорски и бачки,

1708–1709)

46. Исаија Ђаковић (митрополит крушедолски, 1708)

47. Софроније Подгоричанин (митрополит крушедолски, 1710–1711)

48. Викентије Поповић Хаџилавић (митрополит карловачки, 1713–1725)

49. Мојсије Петровић (митрополит београдско-карловачки, 1726–1730)

50. Викентије Јовановић (митрополит београдско-карловачки, 1731–1737)

51. Арсеније IV Јовановић Шакабента (патријарх пећки, 1741–1748)

52. Исаија Антоновић (митрополит карловачки, 1748–1749)

53. Павле Ненадовић (митрополит карловачки, 1749–1768)

54. Јован Ђорђевић (митрополит карловачки, 1769–1773)

55. Викентије Јовановић Видак (митрополит карловачки, 1774–1780)

56. Мојсије Путник (митрополит карловачки, 1781–1790)

57. Стефан Стратимировић (митрополит карловачки, 1790–1836)

58. Стефан Станковић (митрополит карловачки, 1837–1841)

59. Јосиф Рајачић (патријарх српски, архиепископ и митрополит

карловачки, 1842–1861)

60. Самуило Маширевић (патријарх српски, архиепископ и митрополит

карловачки, 1864–1870)

61. Прокопије Ивачковић (патријарх српски, архиепископ и митрополит

карловачки, 1874–1879)

62. Герман Анђелић (патријарх српски, архиепископ и митрополит

карловачки, 1881–1888)

63. Георгије Бранковић (патријарх српски, архиепископ и митрополит

карловачки, 1890–1907)

64. Лукијан Богдановић (патријарх српски, архиепископ и митрополит

карловачки, 1908–1913)

65. Др Максимилијан Хајдин (викарни епископ сирмијски, 1920–1928)

66. Др Иринеј Ђорђевић (викарни епископ сремски, 1928–1931)

67. Др Тихон Радовановић (викарни епископ сремски, 1932–1934)

68. Свети Сава Трлајић (викарни епископ сремски, 1934–1938)

69. Свети Платон Јовановић (викарни епископ сремски, 1936–1938)

70. Валеријан Прибићевић (викарни епископ сремски, 1940–1941)

71. Арсеније Брадваревић (викарни епископ сремски, 1944–1947)

72. Никанор Иличић (епископ сремски, 1951–1955)

73. Макарије Ђорђевић (епископ сремски, 1955–1978)

74. Др Андреј Фрушић (епископ сремски, 1980–1986)

75. Василије Вадић (Епископ сремски, 1986–)